Does Anybody

Here

Speak Japanese?

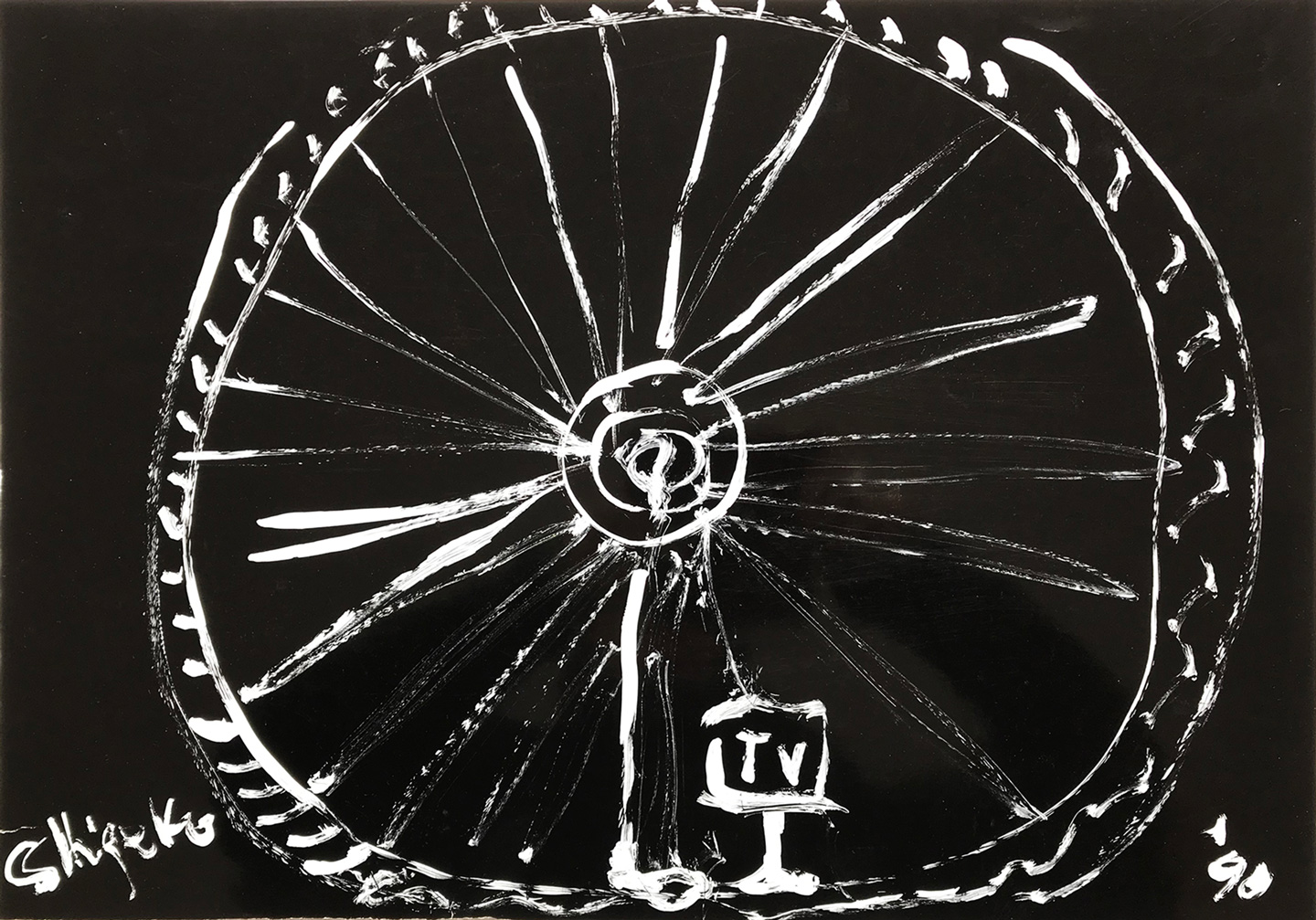

Shigeko Kubota

Ben Patterson

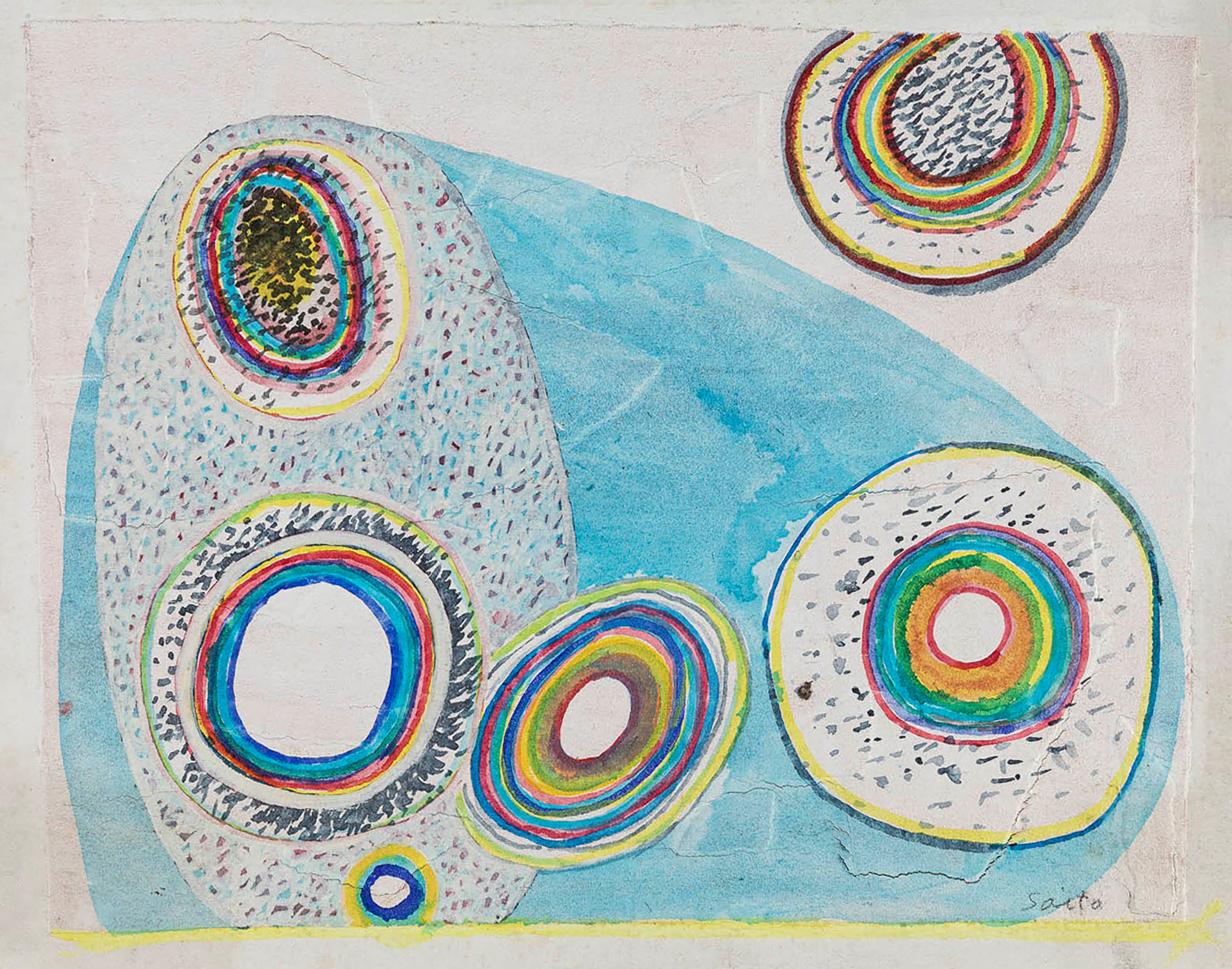

Takako Saito

Fluxus is frequently described as both an international and an intermediary avant-garde movement: In the 1960s, Fluxus actions not only encompassed at least three continents – America, Asia, and Europe – but also had the ambition to work across classical artistic media, by artists of all disciplines as well as non-professionally trained art practitioners. Takako Saito, for example, studied child psychology and professionalized artistically through the Sōzō biiku undō (Sōbi) movement in Japan in the 1950s, eventually moving to New York in 1963, while Ben Patterson initially worked as a trained contrabassist in various orchestras in America and Europe in the 1950s, then devoted himself to performance in the 1960s, and finally, back in New York, pursued a degree as a librarian. Shigeko Kubota, after studying sculpture in Japan, also moved to New York in 1964. There she joined the Fluxus movement and continued her art studies.

The three artists Kubota, Saito and Patterson are united by an artistic strategy of the intermedial, which was and is also influenced by their transnational experiences. This cosmopolitanism of the three can quickly be romanticized as a new, enriching or otherwise positively occupied potential to dive into other cultures again and again. However, on closer inspection, these shifts between continents and countries must at least be classified as ambivalent: Patterson, for example, has had experiences with racism throughout his life, up to and including professional exclusions as a professional musician and thus forced changes of country, and has repeatedly addressed these experiences anew in his works, while Kubota and Saito, with their move, left a narrow, patriarchal Japanese culture and were seeking in New York the possibility of exploring their self-empowerment as women and artists. But here, too, all three encountered limitations-Ben Patterson the New York avant-garde’s lack of interest in supporting the concerns of black people, Shigeko Kubota and Takako Saito the structural limitations not only of immigration laws but of Western varieties of chauvinism.

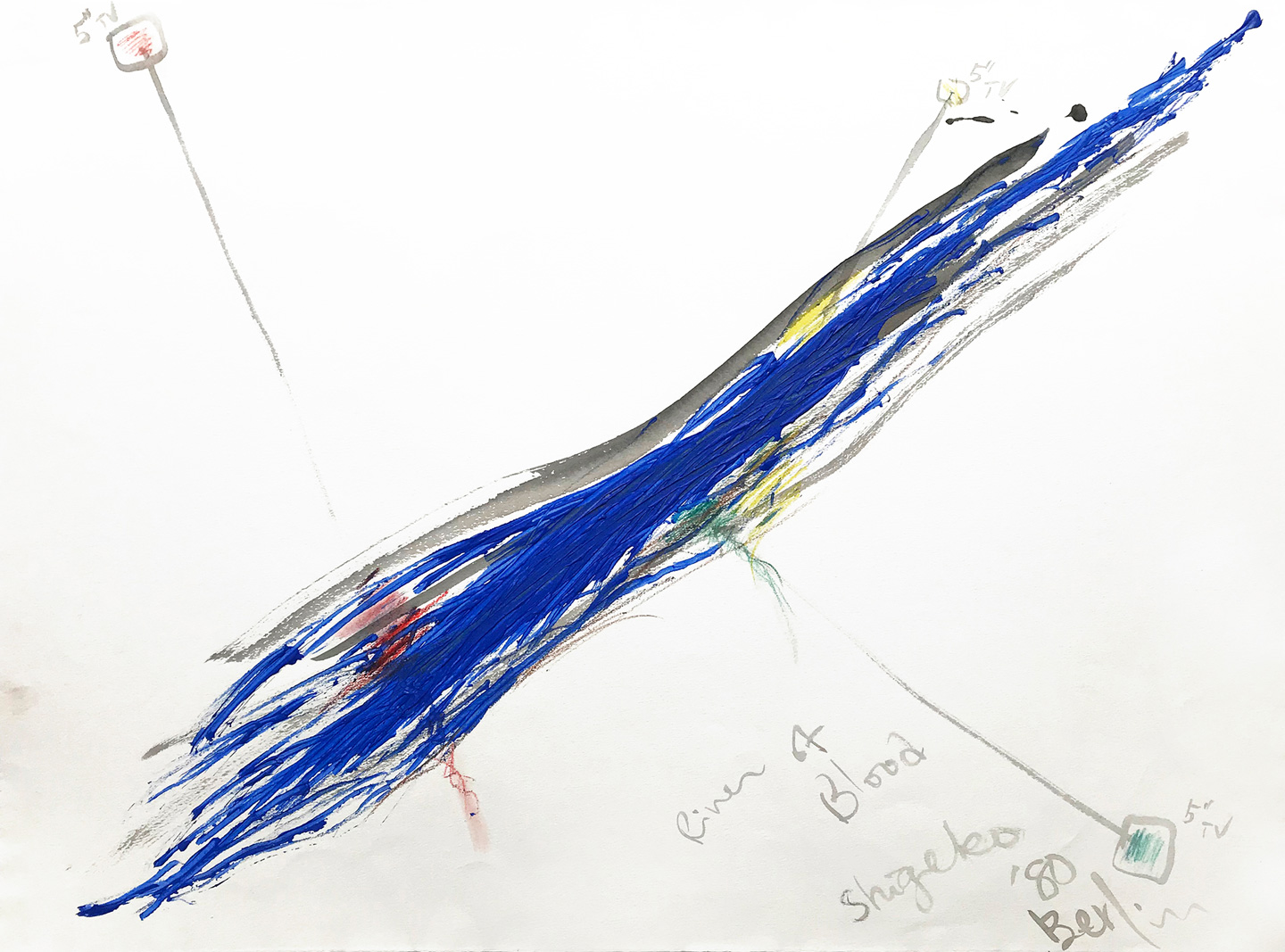

The artist Shigeko Kubota, who was born in Japan in 1937 and died in New York in 2015, was a pioneer of video art. Coming from a family of Japanese monks and temple guards, she studied sculpture at Tokyo University of Education, where she received her diploma in 1960. Following her first solo exhibition „1st Love, 2nd Love…“ (1963) at the Naiqua Gallery in Tokyo, she moved to New York in 1964 at the invitation of Fluxus founder George Maciunas. There she created her first performance „Vagina Painting“ as part of the Perpetual Fluxfest (1965). Later Kubota emancipated herself from her Fluxus-influenced artistic environment and turned to video art. Inspired by her intense encounter with Marcel Duchamp, she developed the first video sculptures which are still considered one of the most important and first representatives of this genre. Long overshadowed by the fame of her husband Nam June Paik, her artistic legacy was appropriately honored in 2022 at the National Museum of Art, Osaka, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, and MoMA, New York, among others.

In the surrealistic video diary „Video Girls and Video Songs for Navajo Sky“ created by Kubota in 1973, the artist impressively recounts her transcultural experience on the Navajo reservation in Chinle, Arizona, which she visited for the duration of a month at the invitation of fellow artist Cecilia Sandoval and her family. During this stay, she developed a friendly bond with some of the reservation’s inhabitants. Reading Kubota’s accounts of her stay, one might conclude that her Japanese heritage was one reason for this unusual familiarity. The artist quotes an elderly Navajo man in her report: „Oh, poor Japanese, you traveled so long to such a small islands, you should have stayed here in America“ I laughed. This old man thinks that the Native American immigrated to China and founded Chinese civilization in 4000 B.C.“ Kubota processes her transnational experiences in her video and transcends cultural identities by blurring the lines between the countries Japan – America and the languages Japanese and Navajo.

„In Kubota’s hands, video is no longer a proposition that is based on veracity, but instead, it is a site where there are no contradictions for what is at stake is time itself, both as it flies and as it stands still.“ Vision in Ruins By Michelle Yap Dizon 2011

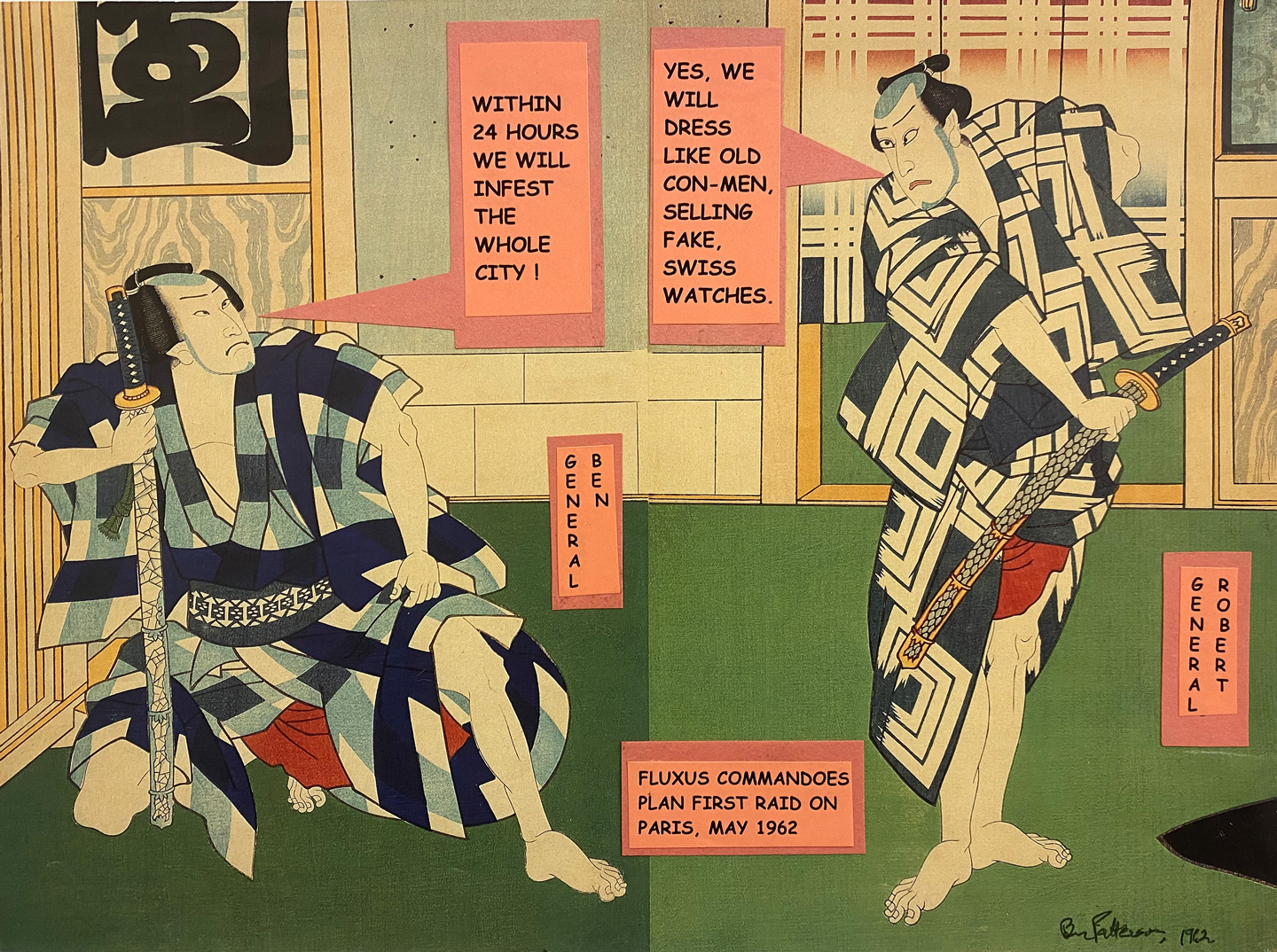

Although Benjamin Patterson, the musician, composer, performance and visual artist who was born in Pittsburgh in 1934 and who passed away in Wiesbaden in 2016, played a central role in the founding of Fluxus, it took him a long time to receive the artistic recognition in the United States that he and his work deserved. “Born in the State of FLUX ” in November 2010 at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston was the first significant museum exhibition in his home country dedicated to his work. Already disadvantaged as a Fluxus artist by the predominantly commercial exhibition and acquisition policies of museums, he was doubly disadvantaged as an African American artist. Even in the close environment of his Fluxus colleagues he experienced an irritating exclusion, the root of which was located in the unsolidary attitude towards the Black Power movement. Valerie Cassel Oliver, in her essay “The Curious Case of Benjamin Patterson,” refers aptly to “this physical reality of his blackness felt for the first time for Patterson among his liberal friends.“

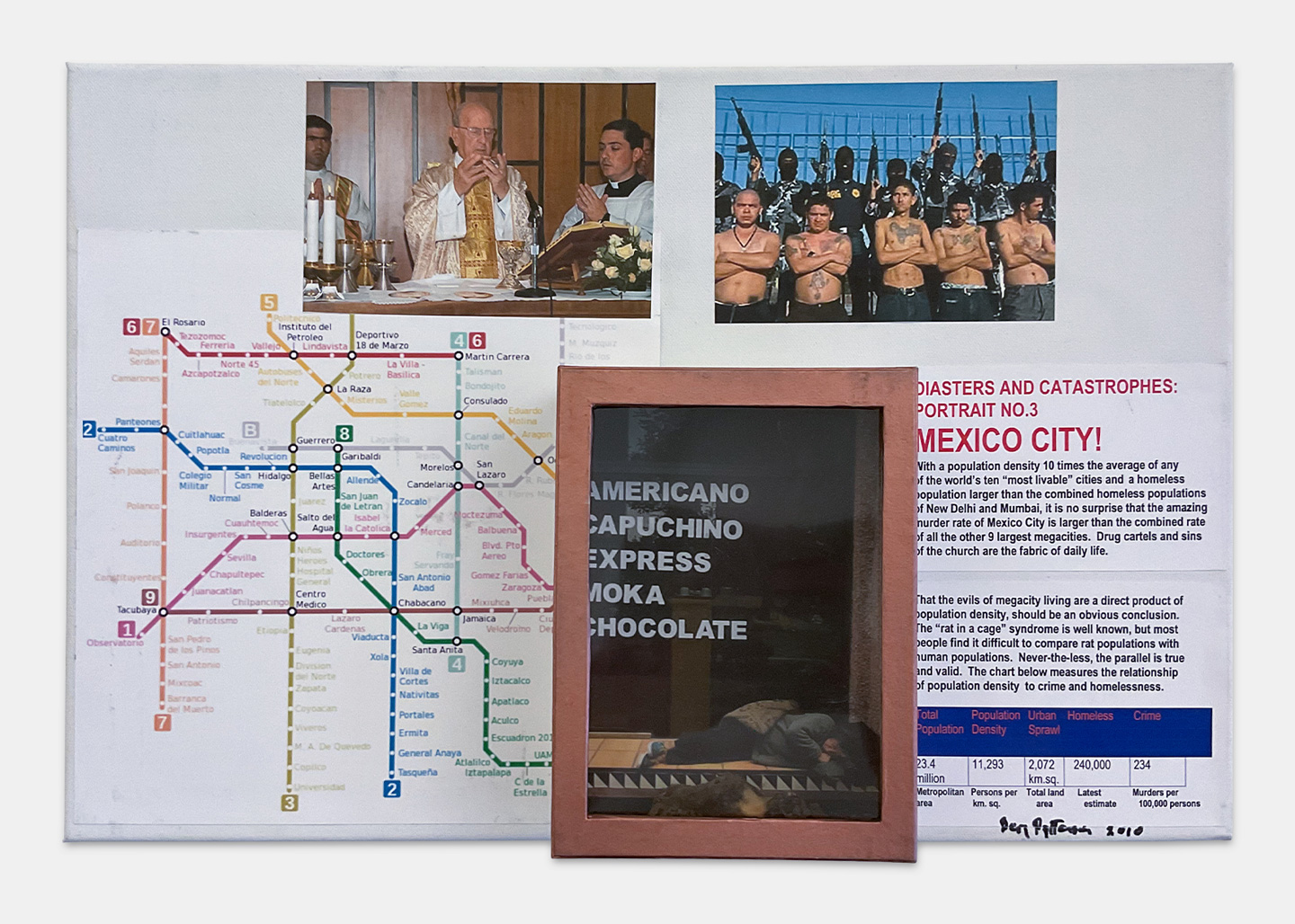

It is not surprising that the artist addressed these experiences in his work. Known primarily for his performative and sound-based pieces, Ben Patterson has created a variety of images and objects that mostly focus on issues of social inequality, racism, and politics in a very immediate way.

Social exclusion is the central theme of his series „Diasters and Catstrophies“. In 2010, Patterson created this series of portraits of various megacities, including Tokyo, New York City, New Delhi, Mumbai, Mexico City, and São Paulo. Assemblages of photocopies, network maps of public transportation and texts on which are placed alongside “dioramas of misery”. By means of photographs and marzipan bodies formed by the artist himself, these dioramas give us a glimpse of the darker sides of these megacities. Patterson himself wrote about these bodies formed by himself from marzipan that lie in front of pictures of homeless people: „Perhaps you are also wondering, why I chose to work with marzipan. One answer might be, that our sub-conscious reaction (mouth-watering desire to these marzipan figures) over-rides and frustrates our usual reaction to look away, when seeing a homeless person. Our mouth forces our eyes look again at this harsh reality.“

Unlike Kubota and Patterson, Takako Saito’s work has never dealt explicitly with the experiences of alienation and exclusion. Nevertheless, her work has a resonance of her often drastic experiences as an illegal person.

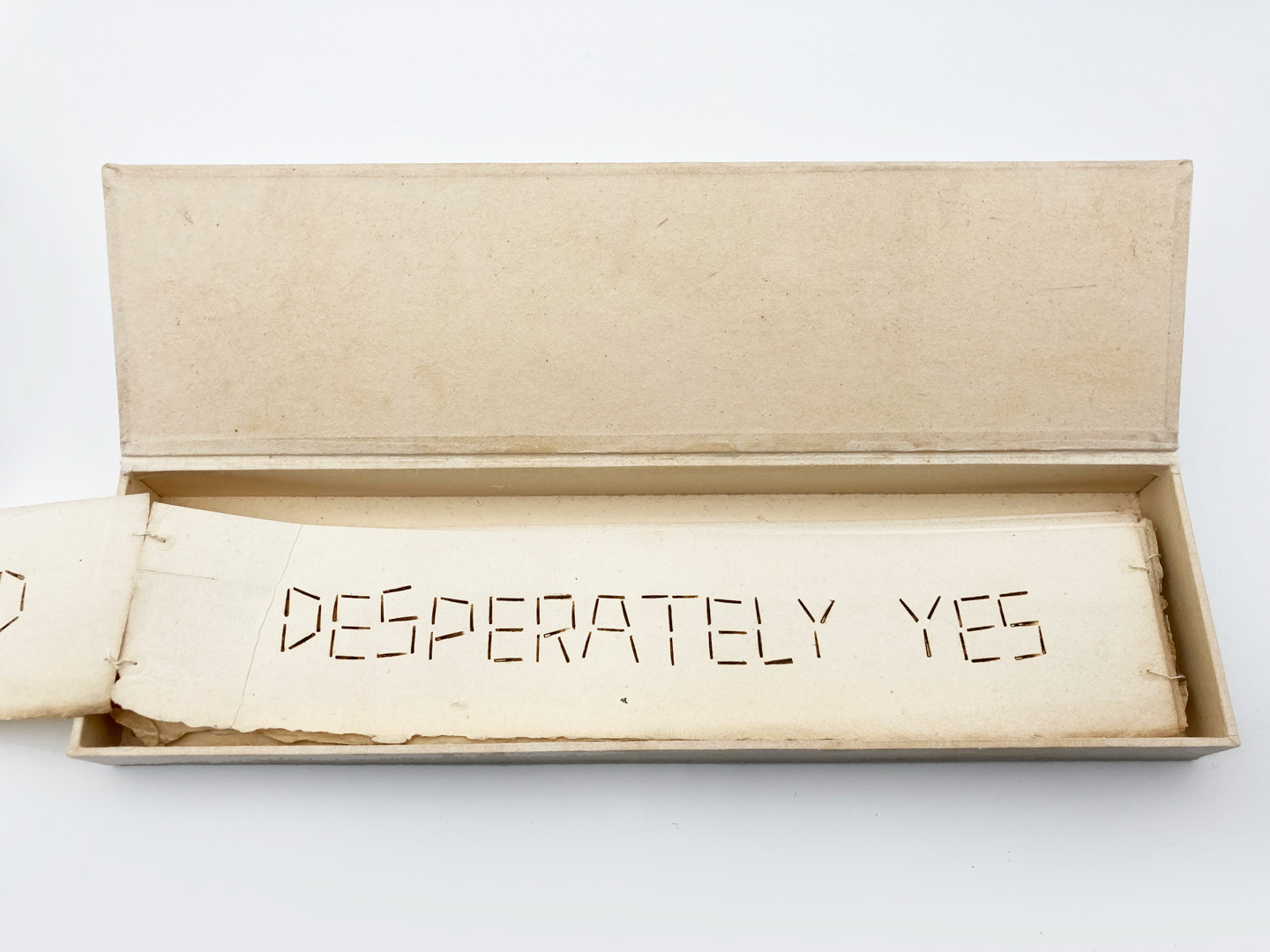

Saito was born into a wealthy family in the town of Sabae in Fukui Prefecture in 1929. As a young teacher, Takako Saito aimed to make a difference in Japanese society. In the 1950s, she became a member of the art education movement “Sozo Biiku Undou.” The goal of this reform movement was to infuse post-war Japan with a playful subtext. In this progressive environment, Saito became acquainted with the artistic avant-garde movements of the time. In 1963, she moved to New York to live a life outside the narrow confines of Japanese society. In New York, she shared an apartment with the artist Ay-O (Takao Iijima), who introduced her to George Maciunas and the Fluxus movement. In the years that followed, Saito explored Fluxus intensively. Play, chance, and the participation of the viewer are principles of Sozo Biiku Undou and Fluxus, albeit in different ways. In the following years Saito lived a partly forced nomadic life. It led her to the USA, France, England and Italy. Countries in which she had to earn her living as a construction worker, cook, babysitter and saleswoman due to her lack of residence permits. Takako Saito, as she herself repeatedly reports, has lived in extreme poverty. The fear of being expelled from her country of residence was her constant companion. Her journey of privation finally took her to Düsseldorf, where she has lived and worked since 1979. Her residential studio on the outskirts of Düsseldorf is an impressive Gesamtkunstwerk, combining her diverse life experiences and her enormous ongoing creative power.

Takako Saito is a tireless worker, even at the ripe old age of 94 she gives several performances a year and manages major museum exhibitions. The perfection of the craftsmanship with which she creates objects, books, and her performance dresses point to the Japanese tradition of craftsmanship, but also to the fact that she has always had to do the production herself for reasons of cost. This enforced frugality, the use of trash and everyday materials is often attributed exclusively to the Fluxus context, but is equally due to her lack of financial means.

Language is a great artistic potential with which Takako Saito repeatedly defies barriers and overcomes boundaries. In her works, for example, she uses English, German, French, Japanese, and Italian, among other languages. In her performances, she often uses a kind of phonetic language that, if one opens oneself to this process, is universal and understandable to all. In her works, Takako Saito connects the world and creates a space for herself and the viewers and co-performers in which nationalities and language barriers no longer play a role.

The exhibition was created in cooperation with the Estate of Benjamin Patterson and the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation.

Opening 31.03.2023 | 6-9pm

open

01.04.2023– 13.05.2023 | Wed–Fri 2–6 pm | Sat 12–4 pm and by appointment

Interested in updates on our exhibitions & events. Sign up for the boa newsletter

Fluxus wird häufig als sowohl internationale, als auch intermediäre Avantgarde-Bewegung bezeichnet: In den 1960er Jahren umspannten Fluxus-Aktionen nicht nur mindestens drei Kontinente – Amerika, Asien und Europa –, sondern hatten auch den Anspruch, quer durch die klassischen künstlerischen Medien zu arbeiten, und zwar sowohl von Künstler*innen aller Sparten als auch von nicht-professionell ausgebildeten Kunstschaffenden. So studierte Takako Saito Kinderpsychologie und professionalisierte sich in den 1950er Jahren künstlerisch über die Sōzō biiku undō (Sōbi) Bewegung in Japan, um schließlich 1963 nach New York zu ziehen, während Ben Patterson in den 1950er Jahren zunächst als ausgebildeter Kontrabassist in diversen Orchestern in Amerika und Europa arbeitete, um in den 1960er Jahren sich Performances zu widmen und schließlich, wieder in New York, einen Abschluss als Bibliothekar anzustreben. Shigeko Kubota zog, nach einem Studium der Bildhauerei in Japan, ebenfalls 1964 nach New York. Dort fand sie Anschluss an die Szenerie der Fluxus-Künstler und setze ihr Kunst-Studium fort.

Die drei Künstler*innen Saito, Patterson und Kubota verbindet eine künstlerische Strategie des Intermedialen, die auch durch ihre transnationalen Erfahrungen geprägt war und ist. Schnell kann diese Weltgewandtheit der drei romantisiert werden, als ein neues, bereicherndes oder anders positiv besetztes Potenzial, immer wieder neu in andere Kulturen einzutauchen. Jedoch müssen beim genaueren Hinsehen diese Wechsel zwischen den Kontinenten und Ländern zumindest als ambivalent eingeordnet werden: So hat Patterson zeitlebens Erfahrungen mit Rassismus gemacht, bis hin zu beruflichen Ausschlüssen als Profimusiker und damit erzwungenem Länderwechsel, und diese Erfahrungen in seinen Arbeiten immer wieder neu thematisiert, während Kubota und Saito mit ihrem Umzug aus einer engen, patriarchalen japanischen Kultur ausgetreten sind und in New York die Möglichkeit suchten, ihre Selbstbestimmtheit als Frau und Künstlerin auszuloten. Doch auch hier stießen alle drei auf Begrenzungen – Ben Patterson auf das geringe Interesse der New Yorker Avantgarde, sich für die Belange von black people einzusetzen, Shigeko Kubota und Takako Saito auf die strukturellen Limitierungen nicht nur von Einreisebestimmungen, sondern der westlichen Varianten des Chauvinismus.

Die 1937 in Japan geborene und 2015 in New York gestorbene Künstlerin Shigeko Kubota war eine Pionierin der Videokunst.

Die aus einer Familie japanischer Mönche und Tempelwächter stammende Künstlerin studierte Bildhauerei an der Pädagogischen Universität Tokio wo sie 1960 ihr Diplom erhielt. Nach ihrer ersten Einzelausstellung “1st Love, 2nd Love…” (1963) in der Naiqua Gallery in Tokio, zog sie 1964 auf Einladung des Fluxus-Gründers George Maciunas nach New York. Dort schuf sie ihre erste Performance “Vagina Painting” im Rahmen des Perpetual Fluxfest.

Später emanzipierte Kubota sich von ihrem Fluxus geprägten künstlerischen Umfeld und wandte sich der Videokunst zu. Inspiriert von ihrer intensiven Begegnung mit Marcel Duchamp entwickelte sie die ersten Videoskulpturen. Bis heute gilt sie als eine der wichtigsten und ersten Vertreterinnen dieses Genres. Lange überstrahlt vom Ruhm ihres Mannes Nam June Paik wurde im Jahr 2022 ihr künstlerischer Nachlass angemessen gewürdigt, u. a. im National Museum of Art, Osaka, im Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokio und im MoMA, New York.

In dem in 1973 von Kubota geschaffenen surrealistischen Videotagebuch „Video Girls and Video Songs for Navajo Sky“ erzählt die Künstlerin auf eindrückliche Weise von ihrer transkulturellen Erfahrung im Navajo-Reservat in Chinle, Arizona, das sie auf Einladung ihrer Künstlerkollegin Cecilia Sandoval und deren Familie für die Dauer eines Monats besuchte. Während dieses Aufenthalts erwuchs eine freundschaftliche Bindung zu einigen Bewohner*innen des Reservats. Liest man Kubota Berichte zu ihrem Aufenthalt könnte man den Schluß ziehen, das ihre japanische Herkunft ein Grund für diese ungewöhnliche Vertrautheit war. Die Künstlerin zitiert in ihrem Bericht einen älteren Navajo-Mann: „Oh, arme Japaner, ihr seid so lange zu so einer kleinen Insel gereist, ihr hättet hier in Amerika bleiben sollen. Ich habe gelacht. Dieser alte Mann glaubt, dass die amerikanischen Ureinwohner 4000 v. Chr. nach China eingewandert sind und die chinesische Zivilisation gegründet haben.“ Kubota verarbeitet in ihrem Video ihre transnationalen Erfahrungen und überwindet die kulturellen Identitäten, indem sie die Grenzen zwischen den Ländern Japan – Amerika und den Sprachen Japanisch und Navajo verwischt. „In Kubotas Händen ist das Video nicht länger ein Vorschlag, der auf Wahrhaftigkeit beruht, sondern ein Ort, an dem es keine Widersprüche gibt, denn was auf dem Spiel steht, ist die Zeit selbst, sowohl wenn sie fliegt als auch wenn sie stillsteht.“ Vision in Ruins By Michelle Yap Dizon 2011

Obwohl dem 1934 in Pittsburgh geborenen und 2016 in Wiesbaden verstorbenen Musiker, Komponist, Performance- und bildenden Künstler Benjamin Patterson eine zentrale Rolle bei der Gründung von Fluxus zufiel, hat er erst spät die künstlerische Anerkennung in den USA erfahren, die ihm und seinem Werk gebührte. So war „Born in the State of FLUX“ im November 2010 im Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston die erste nennenswerte Museumsausstellung in seinem Heimatland, die sich seinem Werk widmete. Ohnehin als Fluxus-Künstler benachteiligt durch die überwiegend kommerziell ausgerichtete Ausstellungs- und Ankaufspolitik der Museen, war er als afroamerikanischer Künstler sozusagen doppelt benachteiligt. Selbst im nahen Umfeld seiner Fluxuskollegen erlebte er eine irritierende Exklusion, deren Wurzel in der unsolidarischen Haltung gegenüber dem Black Power movement zu finden war. Valerie Cassel Oliver erwähnt in ihrem Essay “The Curious Case of Benjamin Patterson“ treffend „diese für Patterson unter seiner liberalen Freunden zum ersten Mal gefühlte körperliche Realität seines Schwarzseins.“

Es ist nicht überraschend, dass der Künstler diese Erfahrungen in seinem Werk thematisiert hat. Vor allem bekannt durch sein performatives und sein soundbasiertes Werk hat Ben Patterson eine Vielzahl von Bildern und Objekten geschaffen, die sich meist auf sehr unmittelbare Weise mit Themen wie soziale Ungleichheit, Rassismus und Politik befassen.Soziale Ausgrenzung ist auch das zentrale Thema seiner Serie „Diasters and Catstrophies“. 2010 schuf Patterson diese Serie von Portraits verschiedener Megastädte, darunter Tokio, New York City, Neu-Delhi, Mumbai, Mexiko City und São Paulo, Assemblagen aus Fotokopien, Netzkarten der öffentlichen Verkehrsmittel und Texten auf denen sogenannte „Elendsdioramen“ angebracht sind. Diese Dioramen eröffnen uns mittels Fotografien und vom Künstler selbst geformter Marzipankörper einen Blick auf die Schattenseiten eben dieser Megacities. Patterson selbst schrieb zu diesen von ihm aus Marzipan geformten Körpern die vor Bildern von Obdachlosen liegen: „Vielleicht fragen Sie sich auch, warum ich mich für die Arbeit mit Marzipan entschieden habe. Eine Antwort könnte sein, dass unser unterbewusstes Reagieren (köstliches Verlangen nach diesen Marzipanfiguren) unsere übliche Reaktion, sich abzuwenden, wenn wir einen Obdachlosen sehen, aufhebt und verhindert. Unser Mund zwingt unsere Augen, diese harte Realität erneut zu betrachten.“

Anders als Kubota und Patterson hat sich Takako Saito in Ihrem Werk nie dezidiert mit den Erfahrungen des Fremdseins und der Ausgrenzung befasst. Dennoch findet sich in ihrem Werk ein Resonanzraum ihrer oft drastischen Erfahrungen als illegale Person.

Saito wurde 1929 in der Stadt Sabae in der Präfektur Fukui in eine wohlhabende Familie hineingeboren. Als junge Lehrerin wollte Takako Saito etwas in der japanischen Gesellschaft bewirken. In den 1950er-Jahren wurde sie Mitglied der Kunsterziehungsbewegung „Sozo Biiku Undou”. Ziel dieser Reformbewegung war es, das Nachkriegsjapan mit einem spielerischen Subtext zu durchdringen. In diesem progressiven Umfeld lernte Saito die künstlerischen Avantgardebewegungen der Zeit kennen. 1963 übersiedelte sie nach New York, um ein Leben außerhalb der eng gesteckten Grenzen der japanischen Gesellschaft zu führen. In New York teilte sie eine Wohnung mit dem Künstler Ay-O (Takao Iijima), der sie mit George Maciunas und der Fluxus-Bewegung bekannt machte. In den folgenden Jahren setzte sich Saito intensiv mit Fluxus auseinander. Spiel, Zufall und die Beteiligung des Betrachters sind Prinzipien von „Sozo Biiku Undou“ und Fluxus, wenn auch auf unterschiedliche Arten. In den folgenden Jahren führte sie ein zum Teil erzwungenes nomadisches Leben. Es führte sie in die USA, Frankreich, England und Italien. Länder, in denen sie wegen ihrer fehlenden Aufenthaltsgenehmigungen ihren Lebensunterhalt als Bauarbeiterin, Köchin, Babysitterin und Verkäuferin verdienen musste. Takako Saito hat, wie sie selbst immer wieder berichtet, in größter Armut gelebt. Die Angst, aus dem jeweiligen Land ihres Aufenthalts ausgewiesen zu werden, war dabei ihr stetiger Begleiter. Ihre entbehrungsreiche Reise führte sie schließlich nach Düsseldorf, wo sie seit 1979 lebt und arbeitet. Ihr Wohnatelier am Stadtrand von Düsseldorf ist ein beeindruckendes Gesamtkunstwerk, das ihre vielfältigen Lebenserfahrungen und ihre enorme andauernde Gestaltungskraft in sich vereint.

Takako Saito ist eine unermüdlich Schaffende, selbst im hohen Alter von 94 gibt sie mehrere Performances im Jahr und bewältigt große Museumsausstellungen. Die handwerkliche Perfektion, mit der sie Objekte, Bücher und ihre Performancekleider erschafft, deuten auf die japanische Tradition der Handwerkskunst, aber auch darauf, dass sie die Produktion aus Kostengründen immer selbst übernehmen musste. Diese erzwungene Sparsamkeit, die Verwendung von Müll und Alltagsmaterialien, wird häufig ausschließlich dem Fluxuskontext zugeschrieben, ist aber ebenso ihrem Mangel an finanziellen Möglichkeiten geschuldet.

Sprache ist ein großes künstlerisches Potenzial, mit dem Takako Saito sich immer wieder über Barrieren und Grenzen hinwegsetzt. So verwendet sie in ihren Arbeiten unter anderem Englisch, Deutsch, Japanisch, Italienisch und Französisch. In Ihren Performances benutzt sie oftmals eine Art Laut-und Silbensprache, die, wenn man sich diesem Prozess öffnet, universal und für alle verständlich ist. In ihren Werken verbindet Takako Saito die Welt und schafft für sich und die Betrachter*innen und Mitspieler*innen einen Raum, in dem Nationalitäten und Sprachbarrieren keine Rolle mehr spielen.

Die Ausstellung ist in Kooperation mit dem Estate of Benjamin Patterson und der Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation entstanden.

Eröffnung 31.03.2023 | 18-21

offen 01.04. – 13.05.2023 | Mi – Fr 14 – 18 | Sa 12 – 16 und nach Vereinbarung